On The Road with the Elliot Lawrence Orchestra 1946 to 1951.

This is a revised article that was published in the December 2002 issue of the Joslin’s Jazz Journal (JJJ) and the Spring 2003 issue of the IAJRC (International Association of Jazz Record Collectors) Journal. A follow-up article containing the itinerary was published in JJJ and IAJRC (winning an IAJRC award in 2003).

The Elliot Lawrence Orchestra was one of the last dance bands to come on the scene. It offered the youngest bandleader and musicians. When it started on the road, the average age in the band was 21. This article focuses on the beginning of the band and its road band period from 1946 to 1951.

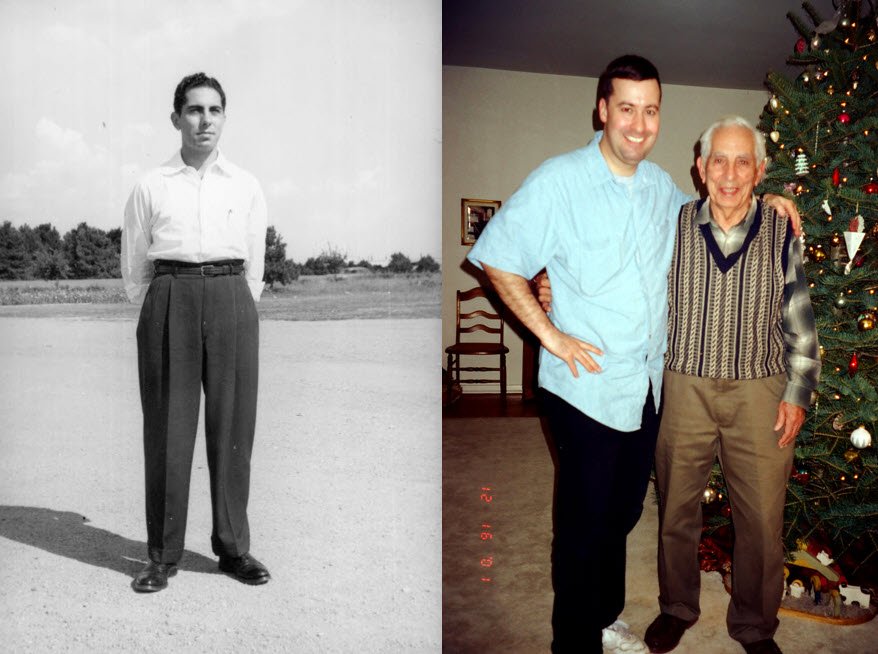

Joe Techner was my father. He had the jazz chair for trumpet in Elliot’s band from November 1948 to July 1951. His solos are on Elliot’s Columbia singles “Elevation” and “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.”

I based the article on my October 1999 personal interview with Elliot at his upper East Side home, with several phone interviews, and interviews of musicians; including Howie Mann at his home in Hicksville, NY, Merle Bredwell at his home in East Sandwich, Mass., Phil Urso, Bruno Rondinelli, and Stan Weiss. A wealth of contemporary newspaper and magazine clippings filled in the gaps where memories had faded.

Elliot Lawrence was born Elliot Lawrence Broza on February 14, 1925. He grew up in Devon, just outside Philadelphia. “My first memories are of music, I was at the piano almost as soon as I could sit up straight,” Elliot recalled. His first public performance was at age 4, conducting a kid band on the Children’s Hour. He began taking piano lessons at the age of four from child specialist Christine Reebe, and by age six wrote his first composition, a tune called “Falling Down Stairs.” Elliot was a veteran of several public appearances when, in 1931, he was stricken with polio (poliomyelitis, infantile paralysis) and for six months fought the illness. After this time, he found that polio had affected the muscles in his fingers. Doctors did not think he could ever resume his short-lived pianist career. Initially, he returned to music by picking up a sax. Then, at the age of 8, he returned to the piano with the help of his mother. His persistence paid off, and at the age of twelve, he formed his first band, a 15-piece unit called the Band Busters.

From 1937 to 1941, he led a children’s band on Philadelphia CBS flag station WCAU on the Children’s Hour, a Sunday show sponsored by the local restaurant chain Horn and Hardart. Since 1928, Elliot’s father, Stan Lee Broza, was an executive at the station, over the years filling the spots of general manager, vice president, and program manager. Although Stan Lee Broza was credited as producer of the show (1928 – 1958), it was Elliot’s mother, Esther, who produced and scripted it, and provided a nurturing home for Elliot. In 1949 she shed light on how she motivated her son to great success, “I firmly believe that if you handle a child with love, instead of sternness, you can get him to do just about anything.”

The Children's Hour – WCAU Television Studio 1948

(Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia)

Elliot told Laura Lee of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin that he owed his success to his mother who kept him at the piano when he wanted to be out playing basketball, by the simple expedient of pulling his hair, “There was only a short time, around the time I was nine years old when I didn’t like to practice. That was the period when I was interested in sports and thought I wanted to be a professional ball player… I’m still interested in sports, but music is the only career I have ever seriously wanted since I was grown up (35).”

Elliot had mastered the piano, saxophone, and clarinet by high school and participated in boxing and wrestling. Elliot continued to do local work with his Band Buster crew, including Rosalind Patton, Bruno Rondinelli, Johnny Dee, Andy Pino, and the Giamo Twins (Mike and Lou). He even wrote the Berwyn High Alma Mater song.

Elliot finished high school at age 16 and entered the University of Pennsylvania on a four-year scholarship. He majored in piano under the tutelage of Erno Barlough. During his sophomore year, he won a statewide competition held by the Penn State Music Teachers Association. His accomplishments at the U. of P. included directorship of the football band, winning the Hurley Cross scholarship - the Alumni prize in music, and the Thornton Oakley Gold Medal for achievement in creative art – the first time a music student awarded it. The Gold Medal was the highest award at the university.

Elliot participated in two Mask and Wig shows, including “Red Points and Blue.” His band, now renamed the Elliot Broza Orchestra, played proms at Villanova and Temple during his junior year. Virginia Polytech, Cornell, Princeton, Penn State and U. of P. featured his band in his senior year. He wrote “A Suite for Animals,” a tone poem submitted to the Philadelphia Symphony for performance during the fall 1944 season. Also, while at Penn, he studied piano and symphonic work under Leon Barzin, a famous New York conductor and composer, who thought so highly of him that he offered Elliot an assistantship. In 1944, after only three years, Elliot graduated at age 19 with a Bachelor of Music and received the school's Art Achievement Award in Music. This award was only the second time in history that the university gave the prize in music.

Elliot remembered he formed his first band at the beginning of World War II, and it played at football games. Members dressed in Penn, Army khaki, and Naval Reserve uniforms; others wore Penn uniforms. The band performed during games at Penn’s Franklin Field in front of audiences of 80,000. Elliot said that in October 1944, this football band appeared on the front page of the Evening Bulletin, the owner of radio station WCAU read it and told Elliot that when he graduated, he wanted him to become music director of the station’s house band.

The owner of WCAU was Leon Levy, president of WCAU Broadcasting Company, Director of Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and its subsidiaries. Leon Levy was the brother-in-law of Samuel S. Paley, known as the founder of the CBS radio and television network. In 1944, Leon Levy was serving in the U.S. Navy and he left his brother, Isaac D. Levy - chairman of the board for WCAU - in charge.

Elliot accepted and took over the band the following January with disappointment that he couldn’t bring many of the Band Busters, “after all this time I’m finally going on WCAU - But without all the fellows I stated with - the fellows I really want to build a great band.”

He did bring on two that he specifically wanted: Johnny Dee and Gerry Mulligan. Elliot’s predecessor was Johnny Warrington, who went on tour. For about a year, Mulligan was writing arrangements for Warrington’s house band.

Elliot letter to Bruno Rondinelli, October 11, 1944. and the Philadelphia Record article.

Elliot spent the month of October excitingly gathering new compositions and arrangements and paid Bruno Rondinelli, away in the army, for some songs. A young Elliot, trying to be hip, wrote the following to Bruno on October 28th, “Here’s the dope on the band – First things I like to have are a few terrific originals… so send me a few sketches.”

On November 1, 1944, Elliot began rehearsing his first studio band for a late evening musical program featuring unique arrangements. The program would weekly highlight a concert number presented first in its original form and then contrasted with a special modern treatment arranged for full orchestra by Lawrence, and featuring his piano.

The Three Dears Trio, a trio of South Jersey girls whose specialty was close harmony. Left to right: Irene Gable, of Camden; Ruthie Melleby, of Merchantville; and Barbara Egan, of Camden. Elliot used the vocal group on his Listen to Lawrence show from January to August 1945.

Elliot debuted on WCAU as the Elliot Lawrence Orchestra at 12:05 a.m. (Philadelphia time) on Friday, January 19, 1945. Following a news update, the band began their weekly half-hour midnight “Listen to Lawrence” broadcast over the CBS radio network. Soloists on ‘Listen to Lawrence’ were baritone Jack Hunter and The Three Dears Trio.” The nightly broadcasts paid sidemen $45.00 per week and $60.00 for pianist/leader Elliot.

The orchestra was composed of three trumpets, three trombones, a French horn, five saxes, and a four-piece rhythm section, including solo piano, orchestra piano, bass, and drums. The station’s budget prevented Elliot from hiring the woodwind players he wanted at the time. However, he was able to hire Ernie Angelucci to play the French horn. Angelucci was formerly with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra.

Elliot got another break when reviewer George T. Simon in New York City heard his midnight broadcasts. Simon flipped the dials at that hour and picked up Elliot. Simon gave Elliot a “rave” review in the March 1945 issue of Metronome magazine. The following year, CBS signed Elliot with a recording contract based on the Simon review and due to the tie that Columbia's Recording Director, Mannie Sachs, had with Leon Levy.

Elliot joined the ranks of Jan Savitt and Joey Kearns as one of the best studio bands to come out of Philadelphia. Elliot began playing high school and college prom dates within a day trip of Philly.

Globe Gazette (Mason City, Iowa) May 31, 1945

Typical selections were “Indiana” – one of the first arrangements that Mulligan got paid for, “The Hunter and The Three Bears,” and “The Old Night Owl,” written by Bruno Rondinelli and named by Elliot. Within six months, Elliot received more than 100,000 fan letters.

When I contacted Elliot, he called Dale K. Craig, who was his young advance manager while on the road, to give me copies of publicity materials to help with me with my article.

Starting with CBS, Elliot’s booking managers published the materials containing a biography of Elliot’s early life and music career. Elliot’s father was Elliot’s manager and probably wrote most of it. Additional publicists included General Artists Corporation, Joe Glaser’s Associated Booking Corporation, and independent agent, David O. Alber.

David O. Alber Associates, Inc. August 1950

The biographies repeat the same story: Elliot was a clean-cut young University of Pennsylvania music student trained in the classics that one day switched to popular music, made appearances at colleges and ballrooms, so the Columbia Broadcasting System gave him both a radio show and recording contract.

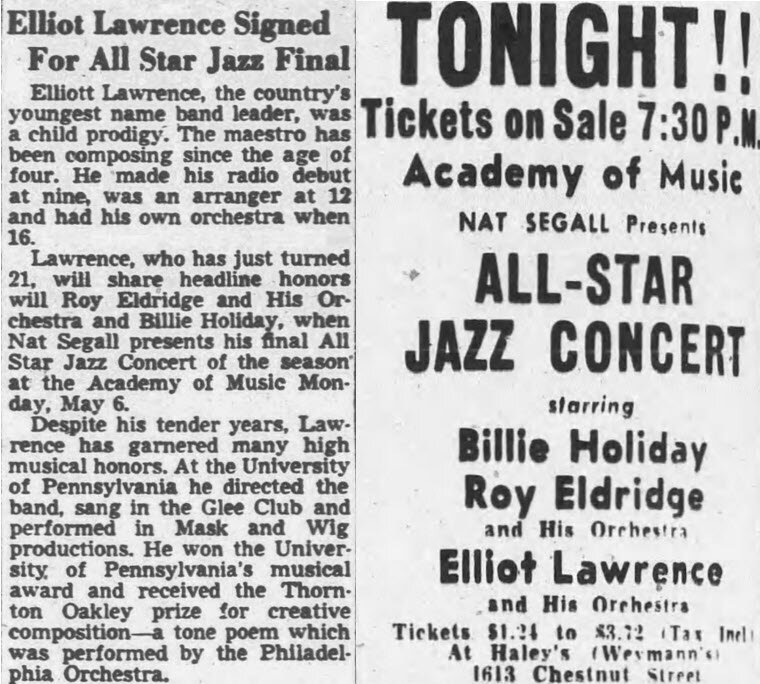

The publicists omitted Elliot’s 1945 and 1946 appearances at Nat Segall’s All-Star Jazz Concerts at the Academy of Music despite newspaper coverage of the jam sessions.

Camden Courier Post April 16, 1946 and May 6, 1946. Elliot’s last appearance with Nat Segall was on May 7th - only six days after he first recorded on Columbia.

In a January 2012 interview with Patrick C. Dorian, Elliot said his band was chosen to open for Dizzie Gillespie and Charlie Parker at the Philadelphia Academy of Music concert. Dorian’s interview is interesting because this is the only time that Elliot seems to mention this appearance.

Segall was the unfortunate operator of the Down Beat Club in Philadelphia that featured Black artists including Dizzy Gillespie. Elliot’s association with the concerts was important because it was here in 1945 that Elliot Lawrence picked up trumpeter Red Rodney, a favorite of Dizzie Gillespie.

The February 11, 1948 Down Beat reported, “The Downbeat, mid-town jam spot where the color line was never in force, either on the bandstand or in admitting patrons, is no more part of Quakertown’s after-dark scene. And all because Nat Segall, who also introduced jazz concerts in classical halls here, refused to fall for the Jim Crow line. Downbeat (the club, that is) was downed during a police ‘clean up’ campaign, which gave them a chance to vent to their racial prejudices, according to Segall. As a result, they closed his room ‘because Negroes and whites mix freely there.’ The Downbeat, a must spot for all visiting musicians, had been known throughout the city as probably the most genuinely inter-racial nitery in the area. Jamming musicians were both white and colored and patronage was about half and half. Segall said the charge of minors being served in his establishment was merely a police screen and that he was being persecuted because colored and white were generally mixed at his place. ‘The Mason-Dixon line has moved up north,’ said Segall, in giving up the famous swing room.”

Here is what the band sound like in 1945 with Red Rodney, trumpet, and Max Spector, drums.

Elliot apparently distanced himself from Segall after pressure from Columbia Records. While I didn’t ask Elliot about Segall, Elliot did share the expectations Columbia put on him after I asked about his later recording of Elevation, a be-bop tune. Columbia wanted to develop Elliot’s band as a dance band featuring ballads.

Elliot’s two early jazz influencers, Red Rodney and Gerry Mulligan, had just left the band and Columbia was not interested in be-bop. Nor was Columbia interested in crossing the line of Jim Crow. Elliot shared billing with Billy Holiday at Segall’s concert. In 1939, Columbia refused to record Billy Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” because they found the subject matter too sensitive. Holiday was under contract with Columbia at the time.

June 1939 Down Beat, pg. 5

Elliot was anxious to please Columbia who awarded him a recording contract and booking management.

Elliot’s initial studio recording work was in February 1946, making Associated transcriptions in New York. On May 1, 1946, the band recorded their first Columbia sides, including “In Apple Blossom Time.” Former bandleader Mitchell Ayres led Columbia’s recording supervisors. Personnel included: Alec Fila, Johnny Dee, Bob Berger (tp) Frank Rodowicz, Joe Verrechico, Tony Lala (tb), Ernie Angelucci (f-hn) Ernie Contonucci, Mike Giamo (as) Gerry Mulligan (ts/arr), Frank Lewis, Andy Pino (ts) Mike Donio (bar) Elliot Lawrence (p/arr) Andy Riccardi or Artie Singer (b) Max Spector (d) Jack Hunter, Rosalind Patton (vo).

Mitchell Ayres

Elliot recalled how happy he was to record for Columbia. George T. Simon noted the following about Elliot in his book, The Big Bands, “Elliot’s faith in people, his desire to please and an apparent lack of self-assurance raised some problems. He could be overly polite, overly receptive. On his record dates, instead of calling Columbia’s recording director “Mitch,” the way other artists did, Elliot would address him as “Mr. Ayres.” So anxious was Elliot to please and to succeed that he would listen patiently to all kinds of advice, much of it conflicting.”

In one of his last interviews, with Marc Myers of JazzWax, Elliot recalled that Columbia had put Ayers in charge of A&R for his recordings and “the trouble with being on Columbia in the early days and later on was that the A&R men wanted a pop sound. I was too young to be a bandleader. You needed more guts to stand up to the executives.”

Ayres made an impression on a young Elliot, but the real one calling the shots was Manie Sachs, vice-president in charge of artists and repertoire (A&R) for Columbia Records. The March 1946 Billboard reported, “Elliot Lawrence ‘s Columbia pact makes his band first one from Philly to get platter contract with a major firm since Jan Savitt’s early days here. Initial record date will be set when Manie Sachs returns from the West Coast.”

Emanuel “Manie” Sacks (Sachs), vice-president of artists and repertoire, Columbia Records

Sachs controlled the pop record industry and his word was final. Because Elliot was inexperienced, Sachs had Ayres supervise.

May 12, 1949 Wilkes-Barre (Pa.) Times Leader

Elliot’s recordings on Columbia that Spring included two of his arrangements; “Five O’clock Shadow” and “Once Upon A Moon” featuring Mitch Miller on oboe and Jack Hunter, vocal. By the end of the month, the Elliot Lawrence Orchestra played the Café Rouge at the Hotel Pennsylvania. Elliot promoted the band as the “Band of 1952.” Despite the lack of any previous “big name” booking, Elliot appeared on twenty radio shows, and his band was on the NBC Chesterfield Supper Club while performing at the Café Rouge over the summer of ‘46.

The Daily Messenger (Canandaigua, NY July 27, 1946

The theme song was “Heart to Heart,” an Elliot original. The reason for naming his theme song was his Valentine’s Day birthdate. The band’s address in Devon, Pa. was “Box 155” - the name of another original Elliot arrangement. Elliot’s phone number was Wayne 1577.

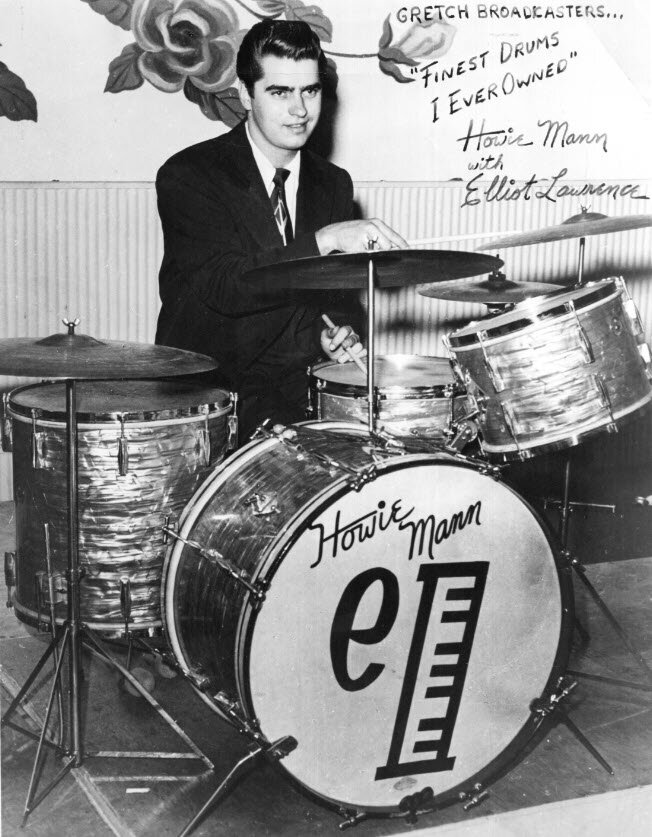

Box 155

As drummer Howie Mann recalled, “Elliot was a top-flight arranger. He gave the band style. You knew when you heard it, that it was Elliot’s.” Besides Elliot, the primary arranger for many of the ballads was former bandleader Frank Hunter. Originally Hundertmark, he officially shortened his name before joining Elliot when he had his own small band. No one knew how to spell it correctly. The last straw was when his band appeared at the Steel Pier. His name didn’t appear on the marquee because it wouldn’t fit. “I provided Elliot ninety percent of his library at WCAU,” Frank Hunter told me in an interview. Hunter left but rejoined the band on the road with Elliot as trombonist and arranger throughout 1949.

Gerry Mulligan would later join Hunter as an arranger for Elliot. Sax player Merle Bredwell later noted, “Elliot and all the musicians he hired were all high-class talented musicians, but even they were not going to be the answer to it. It was the orchestrations that really made the greatest impression, and, as we know, Gerry Mulligan contributed an awful lot to all of his orchestrations and compositions.”

Bredwell also added that Nelson Riddle that did most of the band’s full orchestrations for concerts and theaters. Nelson Riddle was a composer with Elliot in 1946 and arranged the band’s versions of Rhapsody in Blue. While in New York during this time, Riddle also arranged for the Elgart Brothers. At the end of 1946, Riddle left New York and went to Los Angeles, where he arranged for Bob Crosby.

Laura Lee of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reported, “the lyrics of most of his [Elliot’s] pieces are written by Bix Reichner, a Bulletin reporter, with whom he is writing a full-length comedy score.”

That fall, the band went on a nationwide tour. Bruno Rondinelli remembers the starting point for this tour - a one-nighter on September 2, 1946 at Mahanoy City, Pa. just after the Pennsylvania Hotel. Officially, their tour began the next day at Frank Dailey’s Meadowbrook in Cedar Grove, NJ.

The Sunday News September 1, 1946

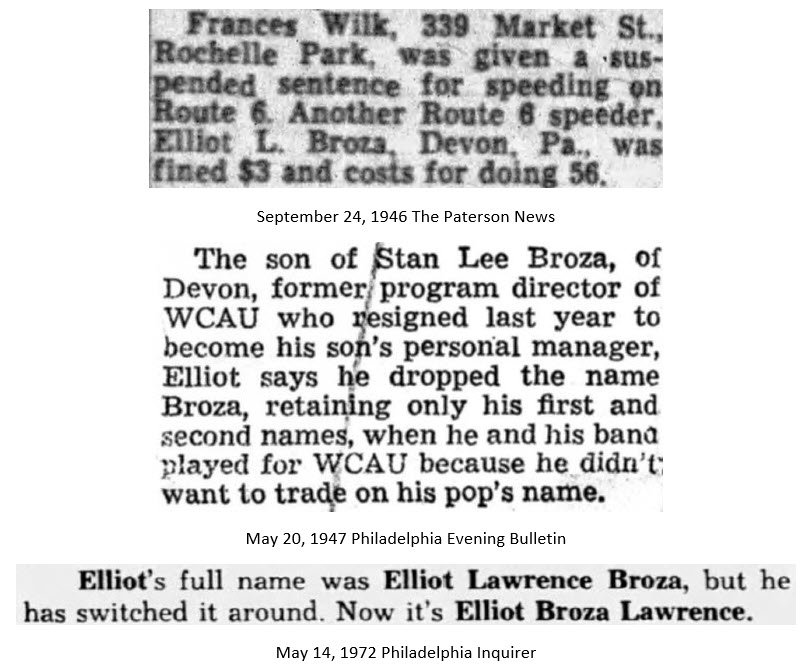

Not long into the tour, the police stopped Elliot for speeding near the Meadowbrook and Elliot gave his last name as Broza.

In 1947, Elliot told Laura Lee of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin that he “dropped the name Broza, retaining only his first and second names.” In 1972, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that his name was now Elliot Broza Lawrence.

In the 2012 Dorian interview, Elliot said his last name was Broza, and “I just officially changed my name to Elliot Broza Lawrence. I switched my middle name to my last name.”

The beginning of October 1946 brought some changes. Elliot introduced a “woodwindette” section composed of bassoon, French horn, English horn, oboe, clarinet, guitar, bass, and the Lawrence piano. Levy was preparing to sell WCAU to J. David Stern. Elliot’s father resigned his program manager post at WCAU to become promotion manager for his son’s band (Pianist Dave Stevens took over the WCAU house band for Elliot’s departure on the road. Stevens would be the last house bandleader at WCAU. The house bands quickly broke up following the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act).

Elliot Lawrence Orchestra personnel highlights: Walt Stuart (Lyszkowski) on trumpet and Vince Forchetti on trombone (both joining June 1946), Marty Masters took over drums, Ex-Band Buster Bruno Rondinelli (tenor) rejoined Elliot after the military, Jerry Field moved to the jazz tenor chair replacing Andy Pino. Giraffe-necked Merle Bredwell (of Beatrice, Nebraska) left Bobby Sherwood to join Elliot playing baritone and alto sax, flute, bassoon, French horn, bass clarinet, and B-flat clarinet. The Elliot Lawrence Orchestra was now a road band performing one-nighters at ballrooms, hotel rooms, proms, and college campuses. The management at Café Rouge didn’t forget how much they enjoyed Elliot over the summer. Upon their request, he returned in late November and played there until Christmas. During his first week, Elliot topped Hotel Pennsylvania’s record gross for the year.

Elliot’s vocal duo was Rosalind Patton and Jack Hunter. Rosalind, who sounded like Helen O’Connell, was born Roselyn Mae Piccurelli in Philadelphia on June 5, 1922. She was an original Band Buster, joining Elliot in 1935. She was 5’2” and served as a WAVE in the Marine Corps during the war. In July 1946, Down Beat reviewer Michael Levin described her as having “a tendency to over-enunciate in an effort to achieve good diction, and also wobbles occasionally with respect to intonation.” Her range was from E-flat to G. Here is Roz in Sympathy.

Rosalind Patton and Elliot Lawrence in Philadelphia. Down Beat magazine, April 8, 1946

Male vocalist Jack Hunter’s real name was John Averona. He was born July 15, 1919, in South Philly. Probably the oldest band-member, he spent five years as a Marine, having joined before Pearl Harbor. He was married to his wife, Marie. Levin’s review; “a quiet but attractive presence, but has a tendency on the stand to be a little different for a man selling an excellent baritone.” His vocal range was from low F to high F. Miriam Spier coached both vocalists. Elliot recalled that Hunter eventually left the band because he was married and wasn’t making enough money.

Despite the changes, the band still had six of the original Band Busters, and half his band members were Philadelphians.

Vocalist Jack Hunter

In December 1946, Elliot signed a contract with Robbins Music calling for him to write at least four original piano compositions during the ensuing year.

The December 1946 issue of The Saturday Evening Post featured trumpeter Alec Fila. in a lengthy article entitled “Sideman with a Horn.” Fila had worked with Jack Teagarden, Bob Chester, Benny Goodman, and Glenn Miller. He had studied under Del Staigers and Max Schlossberg and received a Julliard scholarship. Fila solos on “Five O’clock Shadow.” With the band’s overall lack of experience and age, Fila stood out, and this was what Elliot wanted. Later, in 1952, Elliot revealed the most significant challenge he experienced during the road band days: standing in front of “kids” and maintaining good top-notch musicians while on the road. Having the best musicians he could afford and keep was an obsession to Elliot because it shaped his reputation.

The Post article exposed their readers to the life of a typical dance band sideman. Fila started his day around noon with a milkshake and a sandwich. He spent the afternoon “mooning around, going to a movie or perhaps playing golf,” or doing laundry (washing out socks). Sidemen carried two suitcases for clothes, including the two uniforms they were required to buy. Meals included a sandwich around 6 o’clock and the big meal just before the 9:30-ish big show.

Phil Urso remembered that the guys often got together during free time for a game of touch football at a park near the hotel or a visit to the local amusement park. Denver’s Lakeside Park and Cincinnati’s Coney Island Park were two of their favorites.

Coney Island, Cincinnati amusement park

A union rule forbade them to stay in any hotel for which they were playing. Sidemen often doubled-up in rooms to save expenses, and they “ghosted it” sometimes, as Phil Urso and Stan Weiss remembered. Phil explained that one guy would check in with a razor bag concealing two razors, toothbrushes, and enough toothpaste for the following day. Someone would flip a coin for the top bed and pillow while the other guy slept on a mattress on the floor. Traveling on the road cost money, and this was one way to save a few bucks.

More details into the routine of Elliot’s sidemen are gleaned from the Elliot Lawrence Band Manual that Bruno Rondinelli saved. Elliot prescribed that five bandsmen would travel in each car. A 1-1/2 ton truck transported the instruments and luggage sporting a clothing rack for uniforms. Bulk clothing belonged on the truck. “We allow three hours driving for 100 miles,” and musicians were obligated to arrive three hours before a job. The band reserved rooms in advance. “Of course, there will be no night driving. This is a union law,” Elliot decreed. The boys broke this rule many times over. Elliot paid for each man’s personal, disability and accident insurance premiums. Elliot employed the men in his hometown of Devon, Pa., for insurance purposes, and they all had state unemployment insurance coverage. Musicians insured their personal instruments.

The Manual noted that Elliot held orchestra rehearsals before broadcasts and before each recording. The band had a section rehearsal and one full band rehearsal each week. The Post article noted that, as preferred by the musicians, they held the rehearsals during the week in the wee morning hours after a performance. The band did the daily daytime rehearsals when the band had a couple of days off in a row during a run of one-nighters. However, as Howie Mann remembered, the band often had only about three days off a month, and there weren’t that many rehearsals because the band was traveling a lot, just a lot of warm-ups. Musicians were prohibited from “jamming” less than one hour before a performance but were allowed to warm up backstage or next to the bandstand. Tuning on the bandstand was allowed fifteen minutes prior to playing. While in New York, Elliot often conducted his daytime rehearsals at Nola Studios, 113 W. 57th St.

When the band was free, it was usually on Monday nights because it was the one night that colleges didn’t typically hold dances.

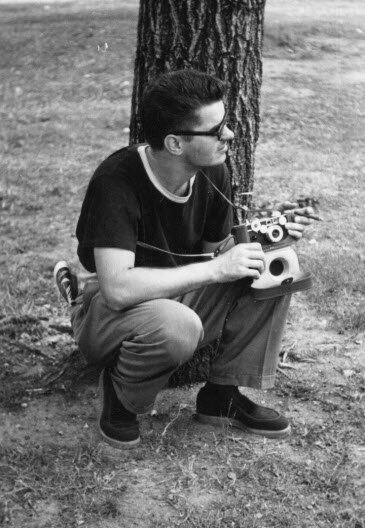

Band members were on a photography kick. Here they are shopping in a camera store in a town somewhere on the road.

Both Elliot and all the boys in the band hated the one-nighters. Howie Mann remembered that sometimes they finished a late-night gig and had to drive all night for a concert in the morning. Howie described working the one-nighters in my interview. Sometimes their meal was a Coca-Cola drink and a package of cookies from a service station. Other times they had plenty of time to relax and prepare for their next performance. During these times, as Phil Urso remembered, they were able to check in to the hotel, clean up, put on their red jacket and ask at the desk where the gig was. The guys looked forward to the few opportunities they had to stay in one place for a few weeks. This is why they forgot playing the many one-nighter ballrooms and proms but still remember the Hotel Pennsylvania, the Hotel Roosevelt, Galveston’s Pleasure Pier, Bop City, the Blue Note and the Paramount Theater at Times Square. The reason why they played so many one-nighters was because the colleges paid the most money.

An interesting note about the Paramount; the band was raised on a platform from a “pit” below the stage. The platform had fixed sold-wood music stands and chairs. The musicians were stuck on these platforms during their hour shows and the whole time worried that they would fall off if they moved just a few inches. It was a fifteen-foot drop. Howie Mann hovered in his seat on the platform above the piano with no back support. He had an eighteen-foot drop.

The basic uniform for Elliot’s sidemen was a maroon cardigan, gray pants, white shirts and a multi-colored bow tie that Elliot’s mother designed. The Band Manual added that musicians would carry a white handkerchief in the suit coat breast pocket, dark socks, and shined browned shoes. Howie Mann recalled additional uniforms including a tan suit with straight tie; a navy blue suit with straight tie or bow tie for formal jobs; and a brown corduroy jacket tailor made by Fox; a “hip” tailor in Chicago.

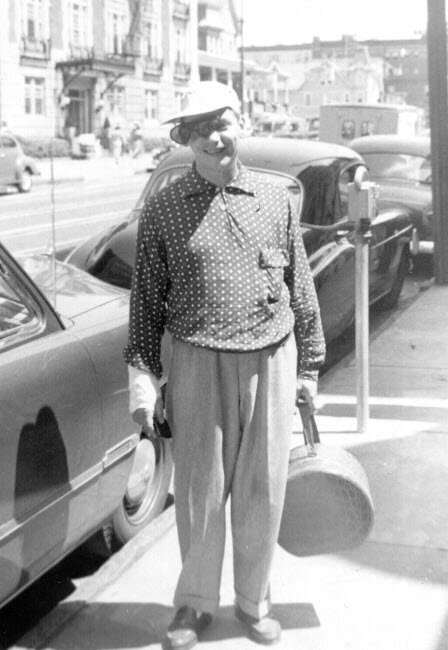

Elliot wore purple plaid jackets, yellow monogrammed shirts and flowered ties. Arnold Fine of the Washington, D.C. Daily News noted, “He seems a likable youngster, normal in every respect – except for the colorful ties and sporty jackets he wears.” Reviewer Michael Levin criticized the leader’s appearance, “occasionally as a result of nervous tension, he turns on a smile of such intensity that casual observers say migawd he must be a phoney – nobody can show that much teeth and mean it.”

Elliot paid musicians union scale that progressed over the years from $110 to $150 a week in cash. Merle Bredwell made a few dollars more to cover the cost of driving his own car (including nine cents a mile reimbursement and being the “road manager.” From their wages, personnel had to pay for their own meals and lodging. Sam Santell was the original road manager and was brought over from the George Paxton band. (Leonard Stevens temporarily replaced Santell as road manager during the band’s Hollywood stay). Then sometime about 1949-1950, Bredwell replaced Santell as road manager. During this time, it was really Bredwell’s wife Lynn that did most of the work. These managers would tend to the business of bookings, transportation and public relations. They called ahead to hotels and mapped out the drive and obtained road information from the American Automobile Association (AAA). “An organization literally on wheels is a complex affair,” noted Elliot.

Tom O’Neil watches Merle Bredwell change a tire at a motel

“He travels about 100,000 miles by car every year, is in a different town almost every night of the week, works six nights a week and sometimes seven, has been in hillbilly towns where it is impossible to get a decent square meal, gone without enough sleep most of his adult life and never had time for girls, yet Elliot Lawrence says he loves his work,” Philadelphia Bulletin writer Laura Lee reported in 1949. He may have loved the work, but Elliot suffered from asthma and allergies while traveling on the road. This would ultimately force him to leave the road.

Some of the band members, like my father, resented Elliot and his frailty due to asthma. He had to drive in a separate air-conditioned car from the rest of the band and had to stay in his own air-conditioned room. But the resentment was mostly because Elliot was exempt from military service due to the severe asthma and most of the band members were World War II veterans.

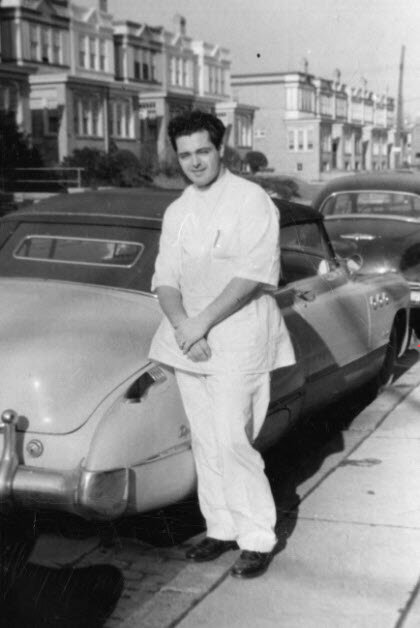

March 1948: Elliot’s bandsmen arrive in Philadelphia in four Buick convertibles.

During the 1947-1948 winter season, the band traveled in five Buick convertibles and a Studebaker truck owned by Elliot and driven by a “band boy,” usually a non-musician, delicately referred to as “instrument man” in the Band Manual.

Ernie Fain, band boy

There were two band boys; Ernie Fain; of Lima, Ohio, and Danny Riccardo, later the male vocalist. In the October 20, 1948 Down Beat, Ernie wrote the editors, “Why do musicians call band boys ‘band boys?’ I myself think it’s wrong. They should have a better title than that. Why not ‘prop manager?’ After all, it’s prop work they do. Some of the prop managers are older than the musicians. In my case, I’m the oldest in my outfit (Elliot Lawrence band) and they call me ‘prop manager.’ They’d better, or else!

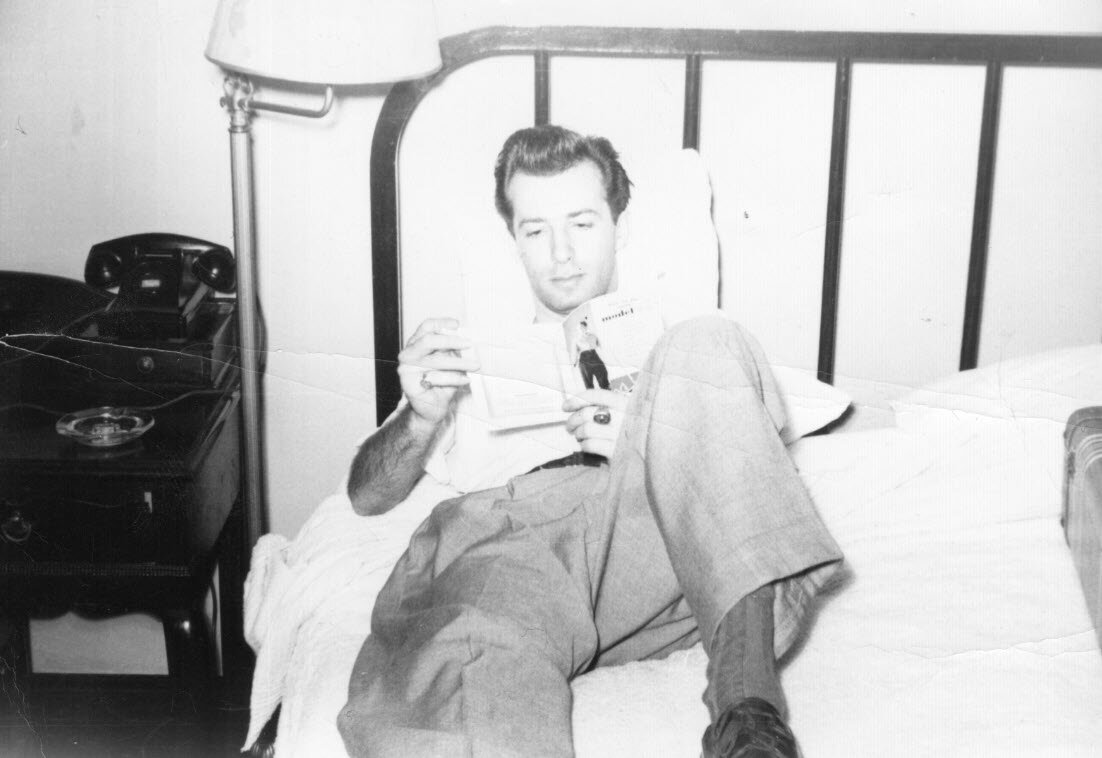

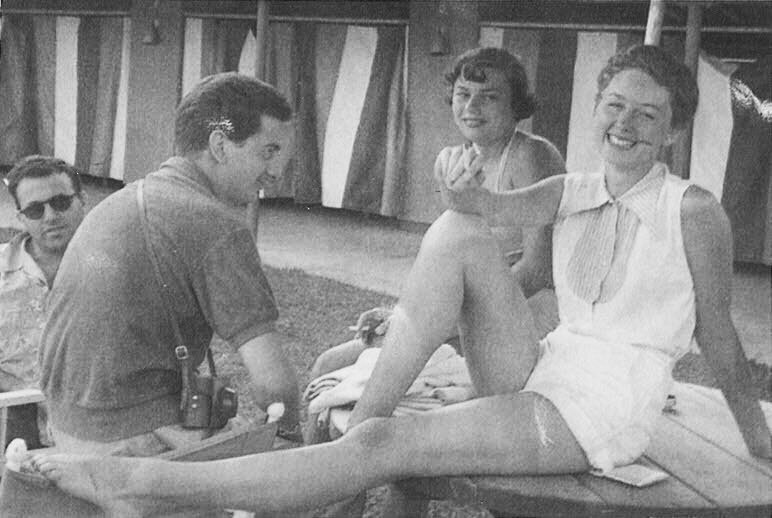

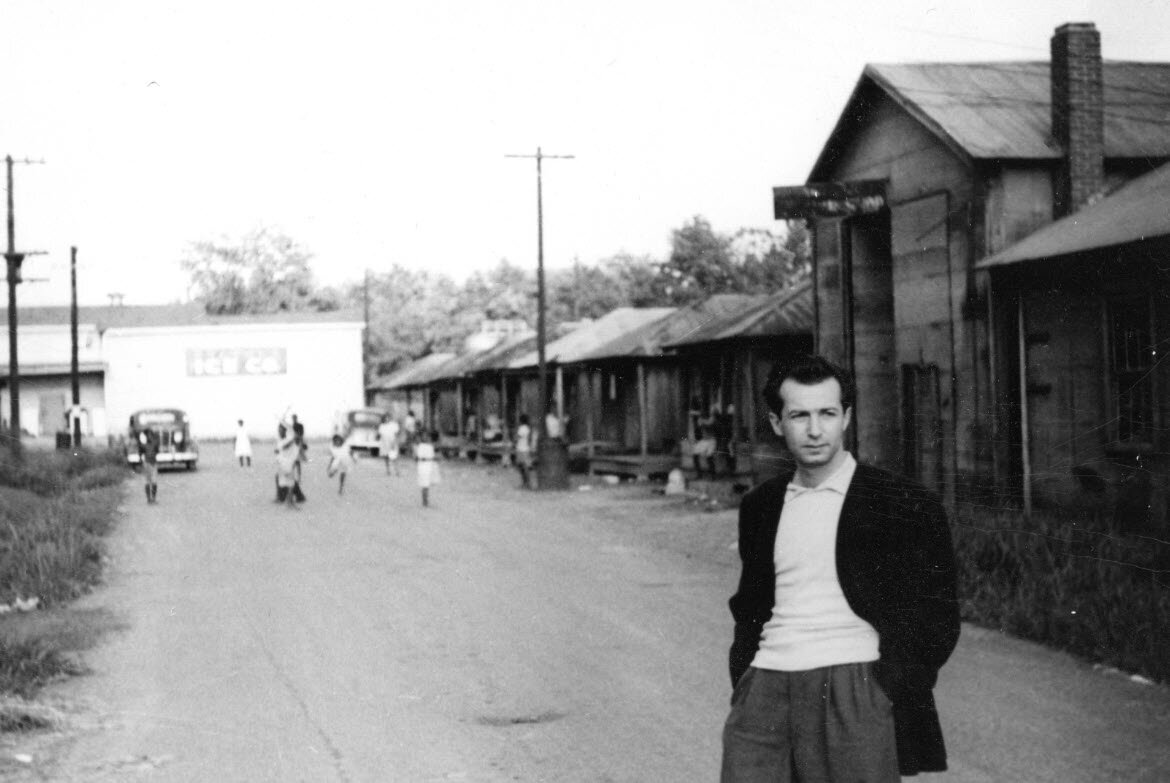

Life on the road: Top (left to right) Howie and his Argus C-3 camera; Johnny Dee and Stan Weiss play cards; Gerry LaFurn chats with girls. Bottom (left to right) Joe Techner reads a magazine in hotel room; Sy Berger, Johnny Dee and Gerry LaFurn talk to more girls. Joe Techner down South.

Elliot used an “advance man” to travel ahead of the band, promoting them to newspapers and radio stations. The first one, Sam Arnold, did not work out. In March 1949, Arnold left the Delbridge and Gorrell agency in Detroit to join Elliot. In early July, Arnold drove to Owensboro, Kentucky late at night and couldn’t find a room. In the morning, he found that the date was cancelled. He drove back to Detroit and quit.

The Owensboro, KY Messenger July 3, 1949

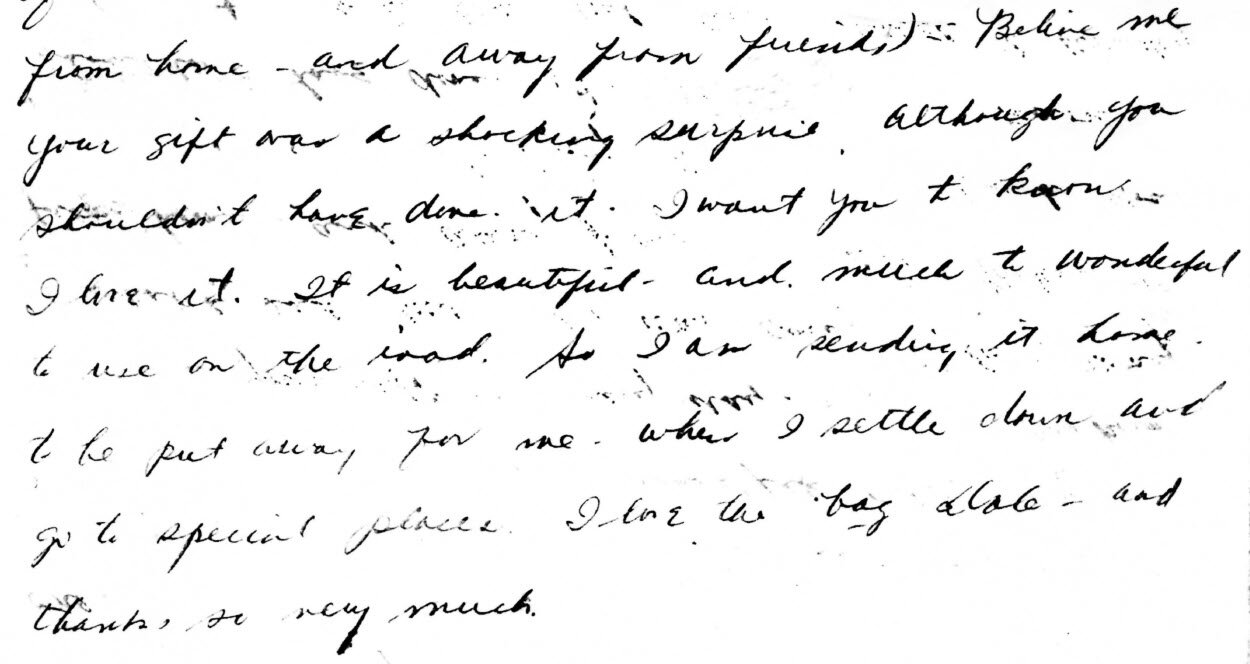

Dale K. Craig replaced Sam Arnold as advance man for Elliot. Craig was a trucker who played sax in army. After military service, he attended Indiana University and was a member of the Sigma Pi fraternity where he reached out to Elliot. Craig was Elliot’s biggest fan and enthusiastically performed advance man duties visiting many radio stations. He also seemed to have a crush on Rosalind Patton and gifted her an expensive bag at Christmas 1949.

December 22, 1949 letter from Rosalind Patton to Dale Craig

In 1952, Craig married a local Indiana girl. Craig’s father founded the truck line Craig Transportation and Craig later went on become a board chairman for the American Trucking Association. Craig worked with Stan Lee Broza and Paul Bannister of the Associated Booking Corporation while advance man for Elliot.

Elliot and Roz with advance publicist Dale Craig

My dad told me that Rosalind wanted to marry Elliot. Another band member told me that Rosalind Patton threw a glass of milk in Elliot's face at breakfast one morning in front of the band. He added that Elliot didn’t like to remember the old days, partially because he didn't want to recall embarrassing incidents such as that.

Joe Techner in front of the Studebaker truck owned by Elliot.

Elliot recalled that Louis Palombi (from New Brunswick, NJ; bass, violin, and tuba) got the Buick autos from a relative who was a salesman at a north Jersey dealership. He got the guys a deal to buy the Buick cars at wholesale cost.

Misfortune reduced the number of Buicks to four on or about January 8-9, 1948, when a drunk driver forced one of the cars off the road at Independence, Iowa. Trombonist Barney Liddell broke a front tooth, and French horn player John Saint-Amour was struck in the lip by a falling radio. His wife, Katheryne (Kay), received minor head injuries. This incident occurred while traveling back east following the band’s stay at the Hollywood Palladium in December 1947.

On that return trip, the truck broke down, and the band missed two dates. Only four Buicks arrived back in Philadelphia for a date at the Click in March 1948.

Other incidents on the return from Hollywood included Johnny Dee leaving the band to help his father, who suffered a nervous breakdown in Philadelphia, and third trumpeter Fred Edwards was out for six weeks after he got a split lip. Three blizzards twice stopped the unit.

December 1947: Elliot at the Hollywood Palladium

Print from an original 2-1/4” negative from Howie Mann)

In mid-1948, most likely because of the return-from-Hollywood misfortunes, Elliot briefly made the band travel by buses. Phil Urso recalled that Elliot wanted the band to travel by bus to keep everyone together and arrive at the date together. But the guys didn’t like it. Merle Bredwell remembers Elliot switched from buses to six autos in late 1948. The drivers were Jimmy Padget. Vince Forchetti, Jack Hunter, Merle Bredwell and Bill Danziesen. Danny Riccardo drove the truck with the instruments. Elliot recalled he was a “road rat.” His real name was Menna Riccardo and he was from Brooklyn. My father rode in Bredwell’s two-tone brown 1948 DeSoto Suburban with Merle and his wife, Lynn. Besides my father, Sy Berger, Tom O’Neill, Howie Mann, and Bob Karch rode with the Bredwells. Stan Weiss also rode in the Bredwell car and noted that they fondly called it “the duck” because its front was shaped like a bill. The sedan had a white leather interior, a rack on top for extra suitcases, and a tied-down canvas and was equipped with an automatic shift but no air conditioning.

Merle Bredwell and his 1948 Desoto Suburban auto (July 1950 photo).

All the men recalled the “well” compartment in the back where they took turns napping during long rides with a pillow. Other times, my father rode in Padget’s car. In 1951, Bredwell switched to a grayish blue 1950 Chrysler Imperial. During the two years that he had the DeSoto, he put 97,000 miles on it. Elliot and Rosalind started out traveling together in a Buick convertible, but, following an accident, they switched to a Cadillac convertible.

Elliot and Roz after finishing a cross-country trip together. Photo by Stan Weiss.

Stan Weiss remembered that Elliot mapped out the routes almost “as the crow flies” for the boys traveling in their cars. Elliot paid the boys nine cents a mile and chose the shortest, most direct route possible. “Sometimes, he had us driving through cornfields,” remarked Stan.

Merle Bredwell, Sy Berger, and Joe Techner looking at marijuana field somewhere in the Corn Belt on one of the blue numbered roads that Elliot paid band drivers, like Bredwell, by the mile. Whole field of it. Merle wouldn’t let the guys fill marijuana in a pillowcase because he didn’t want to take a chance getting arrested. Photo by Stan Weiss

The band traveled several years before the Eisenhower Interstate System was began. Elliot would call ahead to the AAA for travel information. Once, in Tennessee, AAA advised them not to cross the Black Mountains, but they did anyway. They were caught in a traffic jam climbing up a mountain in snow and ice.

“Mount Evans Heatin’ Up” Colorado 1950. Joe Techner is wearing the hat.

In 1951, Elliot recalled how dangerous the roads were, “There are times that we have prayed together. Once we were caught in a blizzard in upstate New York. We wanted to make an engagement in New York City on time, yet, of course, hurrying was impossible. We all were very aware that not a month before, though no one had been hurt, one of our cars had rolled over an embankment. Rosalind, our singer, took out her prayer book. We were all praying. We missed the engagement but got to the city safely.”

Band members Howie Mann and Bob Karch made home movies that capture life on the road. Howie credits these movies for keeping the memories after many years.

The musicians mainly carried Local 77 (Philadelphia) or Local 802 (New York) union cards for Jimmy C. Petrillo’s American Federation of Musicians (AFM). Elliot’s aggregation was predominantly from Philadelphia. Unions were segregated at the time. In Philadelphia, Local 77 was “paleface,” and Local 274 was the “Negro union” Both were AFM. Petrillo was AFM national president based in Chicago from 1940 to 1958.

From being raised by a musician dad, and interviews with his peers, I learned that most musicians don’t see color. Their understanding, expression and appreciation of music elevates above the ignorance and stupidity of our society. And this is what I think of when I listen to “Elevation” - an Elliot Lawrence chart infused with jazz. More about this recording later in this article. Howie Mann, born in raised in Queens, NY, tells us his experience encountering racism down South in 1949.

The Elliot Lawrence Orchestra was one of the few bands that traveled to the Deep South and, as mentioned earlier, Columbia Records didn’t want to challenge Jim Crow. They also didn’t want to be too Jewish, or any other ethnicity. Bandleader Elliot Broza became Elliot Lawrence, drummer Howard Tittman became Howie Mann, saxophonist Mike Goldberg became Mike Gordon, trombonist Vincent Forchetti became Vincent Forrest, trumpet player Walt Lyszkowski became Walt Stuart, arranger Frank Huntertmark became Frank Hunter, vocalist Menna Riccardo became Ricky Riccardo, vocalist John Averona became Jack Hunter, vocalist Rosalind Piccarelli became Roz Patton, saxophonist Berton Herbert Swartz became Buddy Savitt, trumpet player Robert Chudnick became Red Rodney, and so on.

At least one tune was renamed to garner favor of Southern audiences; Mulligan’s “Apple Core” was renamed the “Texas Hop” when they appeared at Galveston’s Pleasure Pier.

Reviewers typed Elliot as a Claude Thornhill clone. While Elliot was at the Café Rouge in 1946, reviewer Michael Levin wrote, “As for the charge that the band imitates Claude Thornhill, Lawrence’s piano playing sounds more like CT than anything else in the band. His use of French horn tends toward a single moving voice with reeds where as Thornhill is more interested in brass section tonalities and ‘room tone.’ Both bands are concentrating on harmonic color overlaid with woodwind delicacy. It’s parallelism of effort rather than copying.”

Elliot responded to Levin, “My piano does not sound like Thornhill’s. Claude concentrates on effects played in the higher register against the band, whereas I play melody on the middle keys.” However, in October 1944, Elliot prepared an Arrangers Guide that stated, “piano is the featured instrument of band, and should be featured in almost every arrangement. The piano will be in the style of Teddy Wilson-Claude Thornhill – light – usually single note right hand – never heavy chorded playing.”

A year later, Elliot’s December 1947 opening at the Hollywood Palladium was reviewed, “Many thought it was great and sat nodding approvingly as Elliot put the band through its paces, yet others felt that although it sounded good, it resembled too closely an illegitimate child born out of Stan Kenton by Claude Thornhill… A few dyspeptic listeners drew the Kenton-Thornhill comparison, but for the most part it was considered a good and welcomed opening.”

Elliot told me, that the band was two kinds; one on the ballad side, somewhat like Claude Thornhill’s band, somewhat moody; and yet on the jazz side was be-bop with Gerry Mulligan writing compositions. Many of Thornhill’s personnel were in Elliot’s band, including Red Rodney, Gerry Mulligan, Gil Evans, and Lee Konitz. “I had every intention of going into symphonic work. However, I started having fun and earning money in the dance field and just stayed there,” Elliot remembered in a 1952 interview.

Elliot’s piano style was suited more for symphonic performances rather than jazz solos. By 1948, Elliot completed a full-length musical score, and Robbins Music contracted for a series of his works for piano studies. Elliot reported Art Tatum as a favorite piano soloist, and his ambition was to compose “classical music.” In 1946, reviewer Michael Levin remarked, “Lawrence himself confines his piano playing to short intervals of melodic snatches. If he is to establish claim to musicianship as well as arranging and leading, there should be more straight piano and a little less cuteness.” Levin again reviewed Elliot at Bop City in January 1950 and stated, “His piano playing was never easy nor flowing, always carried with it a sense of working stiffness that hampered the ideas.” For an illustration of Levin’s points, listen to the original Columbia release of “Elevation.” Then, compare it to the alternate take of “Elevation” recorded at the same session and released on Gerry Mulligan’s posthumous Mullenium album. Bob Karch performs the piano solo on the original release. Elliot does the keyboard work on the alternate take.

In his book The Swing Era, Gunther Schuller said that Elliot was one of the five most interesting big band latecomers who belong more to the modern post-swing period. Elliot shared this distinction with George Paxton, Boyd Raeburn, Georgie Auld, and Randy Brooks.

By the time of Elliot’s arrival on the band scene, “swing music,” popular during the war, was on its way out. In a September 1947 article in PIC, author Dorn Dornbrook wrote, “Swing music is going the way of the Charleston and the Bunny Hug. It’s just a matter of time until the bobby-soxer will be something to tell the grandchildren about, along with the flapper and the red-hot mama.”

What remained on the musical menu were quick-tempo Latin rumbas and sambas, sweet and low dance tunes and the emerging be-bop sound.

Elliot stayed away from the Latin jump tunes. By 1949, Elliot said that rumbas and sambas were “definitely out” on college campuses and elicited no response from the audience.

The sweet sound was Elliot’s primary commercial output. Initially, he favored it and saw it as a medium to ease in his symphonic leanings. “We’re trying to get more classical sounds, Elliot said, “That way we get a sort of purple mood. Overseas, the kids loved wild razz-ma-tazz. But now they’re back, they want to put their arm around their girlfriend and romance slowly.” Among the “classical” selections that Elliot offered were “Chopin’s Prelude in A Major” and Debussy’s “Clair De Lune” (adaptation). At the Café Rouge and Washington’s Club Kavakos, Elliot’s “Heart to Heart” band was advertised as “The Band That’s Sweet with a Beat.”

At the end of 1948, Elliot attempted to shrug the sweet profile when talking to trade pub Metronome, ”We’re not strictly a sweet band, not by any means. Maybe when you hear us in hotel rooms and spots like that you think so, but listen to us on one-nighters and on college dates, and you’ll hear us jump, too. I’d die if we didn’t and so would the guys. Trouble is, though, we’ve been typed, because when we first started at station WCAU in Philly, we had to play a lot of sweet stuff. That’s radio. You know.”

However, the “sweet” sound was Elliot’s popularity. In January 1947, Look Magazine selected Elliot’s ork as Band of the Year. That year, the band grossed a quarter-million dollars. Then, for three years in a row (1947 – 1949), the sweet sound made Elliot the campus choice as the most promising newer orchestra on Billboard’s Annual College Poll. The band also enjoyed high ratings in polls taken by Orchestra World and Billboard, both trade papers. The colleges followed Elliot’s career closely. The University of Missouri’s The Barnyard Post newspaper noted that Down Beat and Metronome put Elliot among the ten best bands in the country. In June 1949, Billboard ranked Elliot as the #7 All-Around Favorite, behind Vaughn Monroe, Tommy Dorsey, Tex Beneke, Les Brown, Stan Kenton, and Guy Lombardo, respectively.

So, on March 16, 1949, three weeks before recording the famous Mulligan arrangement of “Elevation,” Elliot had this to say about bop, “Jump and bop tunes cause dancers to stop and crowd around the bandstand and watch an orchestra perform. They’ll applaud, sometimes. But it’s when they’re able to move around – hold each other close – in a slow, sweet number, that we get our best response.” Elliot said that he had just finished another nationwide tour of colleges, and the colleges preferred sweet and low rhythms.

Paramount Theater March 1949

When Elliot made the above bop-disparaging remark, the band was performing a three-week stint at the Paramount Theater at Times Square with the Nat King Cole Trio. Author Jerome Klinkowitz in his book Listen: Gerry Mulligan, recalled that Elliot’s show at the Paramount opened with a novelty Mulligan arrangement of John Philip Sousa’s “Strike Up The Band.” Drummer Howie Mann fondly remembered those three weeks and recalled that Cole would sit in on piano with the band at the end of every show. The climatic number was always “Elevation. Howie noted that since there were five shows a day, the band drilled this tune about 100 times while at the Paramount, a significant departure from all the ballad work the band played at proms and recorded commercially. After three weeks at the Paramount, the boys in the band decided they had to record it.

Elliot and Nat King Cole share a moment at the Paramount, March 1949

Elliot was playing “Elevation” as early as the Hollywood Palladium days in late 1947. It was purportedly the first tune Mulligan that ever wrote as a teenager in Philadelphia. On January 29, 1947, Red Rodney first recorded it on his Bebop album (Keynote Records). Mulligan later expanded it for Elliot. Although radio listeners heard the Elliot Lawrence Orchestra play it at the end of every broadcast and one-nighter, Elliot had not yet recorded it commercially.

Gerry Mulligan was from the Reading, Pa. area, and Elliot was from Devon, just outside Philadelphia. Mulligan moved to Philadelphia and dropped out of West Catholic High School after problems at home. Elliot recalled that Mulligan stayed in the Broza home for a while. Mulligan and trumpeter Red Rodney had been with the band in 1945 during its infancy. The two left together and joined Gene Krupa in January 1946 without recording commercially with Elliot. While with Krupa, Mulligan wrote arrangements for “How High the Moon” and “Disc Jockey Jump.” Mulligan’s next went with Claude Thornhill. In September 1948, Mulligan left Thornhill to stay in New York City with the Miles Davis Birth of the Cool group (Klinkowitz, pg. 28). While with them, Mulligan played anonymously off and on in Elliot’s sax section when Elliot appeared at the Paramount in March 1949.

Howie Mann recalled "Elevation" as the only memorable recording for the band and remembered the boys had difficulty convincing Elliot Lawrence to record the be-bop tune. The band pressured Elliot and, once he agreed, Elliot had difficulty convincing Columbia’s A&R man Manie Sachs.

In a 1949 interview, Sachs noted the distinct change in the public’s music taste since World War II. “They aren’t interested in loud music, jam sessions or any kind of music that plays away from the melody itself,” he said. “Be-bop hasn’t a chance. It’s a fad. I can’t understand it, and I don’t know anyone else who can explain it and make sense.” he said.

Despite this opposition, Howie said that Elliot came back from Columbia with a deal; the band could record it, but the band members had to personally promote it by going town-to-town, visiting radio stations, and handing out copies. At first, the band thought this was tacky, but they agreed.

During a week in April that the band was initially scheduled off, Elliot secured a recording date. He wrote band members a letter with details for the “Elevation” recording session. On April 12, 1949, the band met at the AFM rehearsal hall at 18th & Arch Streets in Philadelphia. The rhythm section met at 1:45 p.m. A full band rehearsal from 2:00 to 5:00 p.m.

April 12, 1949 rehearsal: Jimmy Padget, Johnny Dee, Joe Techner

April 12, 1949 Rehearsal of “Elevation” at the American Federation of Musicians headquarters rehearsal hall, 120 N. 18th St. in Philadelphia.

Top Row (L to R): Trumpets: Bill Danziesen, Jimmy Padgett, Johnny Dee, Joe Techner; Bass. Tom O’Neill. Front Row: Trombones: Chuck Harris, Vince Forchetti, Sy Berger; Saxophones: Merle Bredwell, Bruno Rondinelli, Joe Soldo, Louis Giamo, Phil Urso. (Not pictured: Drums; Howie Mann and Piano: Bob Karch)

April 12, 1949, Elliot rehearsing the band. Gerry Mulligan standing on Elliot’s right. Columbia executives sitting on bench in background.

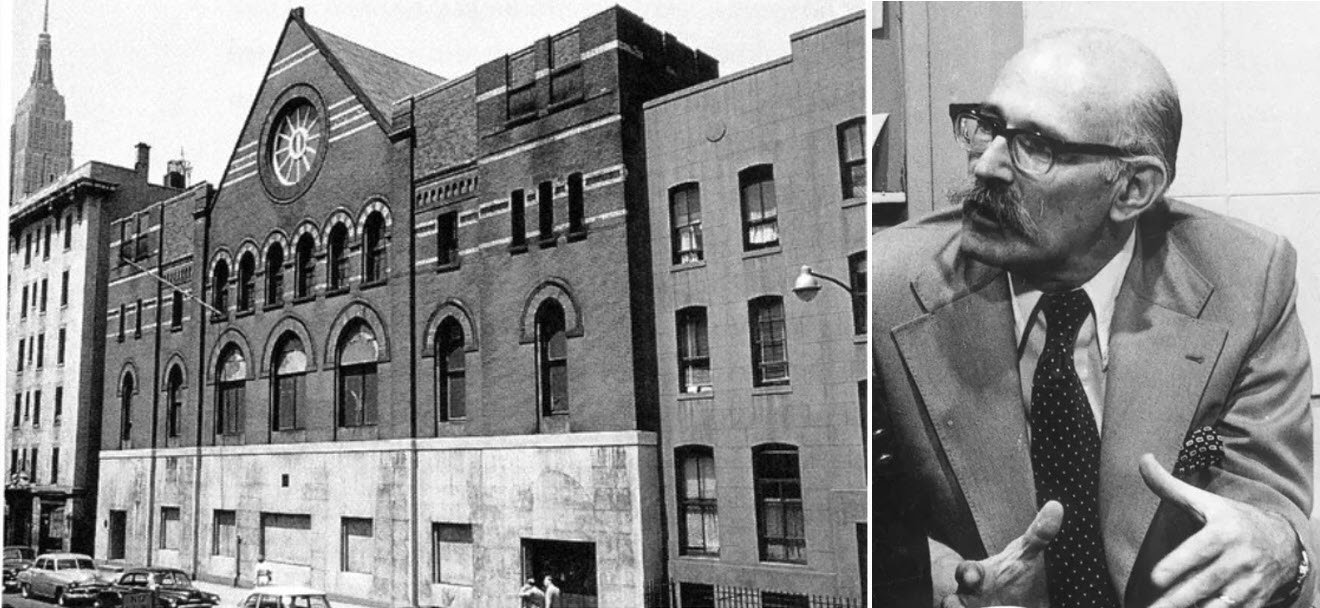

The next day at 1:30 p.m., they began the recording session at Columbia’s 30th Street studio. Columbia purchased the 207 E. 30th Street Midtown Manhattan studio in 1949. In 1998, Columbia engineer Howard Scott remembered the studio; “It was one big room with 45 foot ceilings, about 120 feet long and 55 feet wide.” A 1953 article in Time magazine described the scene, “The stained-glass windows are bricked up, the pews are gone, and in place of the organ there is a glass-fronted control room which bristles with switches, plugs and dials.” The Time article identified the church as the Adams Memorial Presbyterian Church. When Columbia took over the building, it was the Armenian Apostolic Church. Howie Mann describes the studio in my interview.

Left: Columbia’s 30th Street Studio. Reeve’s Audio Recording

Right: Howard H. Scott, who described the studio in Michael Hobson’s article, “The Classic Interview: The Birth of The LP” (The Audiofile, Issue 14, 1998). Photo courtesy The New York Times.

The 30th Street studio was one of the recording industry’s most renowned studios. Howie explained this was because it had a natural echo. My father noted that Columbia selected it because of the extraordinary acoustics that only a large empty church could offer. An apartment building replaced the studio in 1982.

Inside the 30th Street studio in later years. Reeve’s Audio Recording

Columbia’s deal also required Elliot to record two songs that he didn’t want to do; “Gigolette” and “Ev’ry Night Is Saturday Night.”

“Gigolette” (white label radio station copy)

The session’s first cut was “Gigolette,” a ballad using an electronic musical instrument called a “Theremin,” named after a Russian scientist Leon Theremin. The Muncie Evening Press explained, “this instrument is played by passing a wand through two beams of light, breaking the circuit of the two electric eyes. His is the only dance band in the country that has employed this instrument for the weird effects it creates.” Dr. Samuel Hoffman, a chiropractor and former Meyer Davis violinist played it during a Spellbound Hollywood score and won an Academy Award. However, this session had Lucie Bigelow Rosen operating the clumsy instrument, and the results were less than satisfactory. It whimpered around the oboe and bassoon in the ballad background. The band made numerous takes, but the final product was still out of tune.

Lucie Bigelow Rosen showing Elliot how to use the Theremin.

The second cut was “Ev’ry Night Is Saturday Night,” which allowed the trumpet section to warm up. Elliot used a vocal chorus on the record.

Then came time to record “Elevation.” A Down Beat review of “Elevation” noted it was not recorded right,“ With Elevation, you can hear what happens when the boys go hog wild with resonance, and don’t control it properly. I would guess that this record was made in Columbia’s East 30th Street church studios in New York City, with the new Altec Lansing microphone, which has a wide range pickup. Because the session was done without proper attention to control, the entire side is mush, with no definition between sections.”

The recording of “Elevation” that made it on the Columbia sides was later part of the Smithsonian Institute’s Big Band Jazz Collection as one of the top 50 jazz recordings of the 20th century - was a warm-up take meant for setting recording levels. Elliot Lawrence is NOT on the piano as commonly believed. It was the first take, and Elliot was in the control room with Columbia’s engineers checking the sound. Bob Karch is the piano soloist. After performing alternate takes, the band picked the initial recording with Karch on piano as the best. Elliot didn’t object since the record was meant for the boys in the band. Years later, Elliot told jazz veteran Burt Korall, "I believe we got such an excellent performance of ‘Elevation’ because the guys in the band were so happy to have a chance to record it. The company was a little leery about letting us do it. Columbia executives wanted to develop interest in our ballad things rather than our jazz arrangements and soloists."

Korall’s liner notes for Jazz In Revolution eloquently reviewed the recording, “On ‘Elevation,’ Gerry Mulligan's treatment of the blues, the band gives every indication of having matured and fully come to terms with the sounds and rhythms, the language of modern jazz. The score is lean, harmonically interesting (using ninths, elevenths, and augmented elevenths), and compactly made. Based on a long sweeping twelve-bar line over blues changes, it allows sufficient room for soloists Phil Urso, Vince Forrest, Joe Techner, Lawrence [Bob Karch], and Howie Mann to have their say. Excellent ensemble writing tightly links thematic material and solos, giving the work flow and a strong pulse.”

Merle Bredwell also remembered the recording, “I think we made a pretty good recording. I’m sure, you know, when you play the same arrangement every night, and each soloist has maybe a little addition he wants to put into it, it’s going to change from night to night. So, I would say probably there were a lot of other times we played the arrangement – maybe at a dance or a concert – that might have been better than the recording, but still, I think the recording was a blessing for the musicians that were involved in it.”

The following is the personnel for the "Elevation" recording; Joe Techner, Johnny Dee (John DeFrancesco), and Jimmy Padget, trumpets; Sy (Seymour) Berger, Vince Forchetti, and Chuck Harris, trombones; Bill Danziesen, trumpet, and French horn; Joe Soldo, Louis Giamo, Phil Urso, Bruno Rondinelli, and Merle Bredwell, saxophones; Otto ("Bob") Karch, pianos; Tommy O'Neill, (string) bass; Howie Mann, drums. Gerry Mulligan was also present for the recording. It was originally issued on Columbia 38497.

The band members kept their promise to Elliot. The boys in the band visited record stores and radio stations, giving out copies of the record. Howie Mann was probably the most prominent promoter and rushed a copy to Al “Jazzbo” Collins at station KALL in Salt Lake City.

Al “Jazzbo” Collins June 6, 1949 (postmark) letter to Howie Mann

Howie had befriended Collins back in ’47 when the band played at Jerry Jones’ Rainbow Rendezvous. In 1950 Jazzbo moved to New York, where he had the popular late-night program “Purple Grotto” on WNEW. Elliot later remembered that “Elevation” didn’t sell many copies right away.

April 27, 1949, Guelph, Ontario

Top (L to R): Merle Bredwell, Tom O’Neil, Jimmy Padgett, Vince Forchetti, Sy Berger, Howie Mann

Bottom: Joe Techner, Phil Urso, Johnny Dee.

Bop was at its peak during the summer of 1949. The Click in Philly opened in July decorated in bop style featuring Dizzy Gillespie. The band started to pursue the progressive bop style with or without Elliot. Howie Mann, Tom O’Neill, Bob Karch, and Phil Urso formed a combo called “Phil Urso’s Swingsters” and made recordings on the Futurama label.

Frank Palumbo’s Click nightclub, a popular spot in the late 40s.

The decline of the dance bands, the success of “Elevation,” the Mulligan charts, and the creative pressure from the boys in the band all influenced Elliot. He began taking steps to secure the emerging audiences and music styles. Elliot noted, “kids don’t go to the dance halls as much as they used to.” Elliot told the Philadelphia Bulletin that he gave up his free Monday nights to visit high schools to, “acquaint high school students- first hand – with what they’re missing.” The November 4, 1949 issue of Down Beat, Elliot noted that his library was tending more and more toward originals by Mulligan, “I want to be a dance band that’s going ahead,” Elliot said, “I want to play stuff with a modern sound.”

Gerry Mulligan officially joined the band on October 8th and formed his a quintet within the band with Elliot’s blessing. It included Mulligan on baritone sax, Phil Urso on tenor, Tom O’Neill on bass, Howie Mann on drums, and Bob Karch on piano. Among their favorites was “Elegy to a Man” and “The Gold Rush.”

Down Beat magazine, November 4, 1949, page 2

Howie Mann recalled how brilliant Mulligan was. Once, while rooming with Gerry, he went asleep while Gerry was working on an arrangement. When Howie woke in the morning, Gerry was still working on the arrangement. He hadn’t slept at all.

Two days after Mulligan joined, Elliot recorded his last sides on the Columbia label, including an instrumental version of “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea” – a tune typically performed with lyrics by prominent vocal artists. The second cut was “Ritual Fire Dance” - a song not arranged by Mulligan. Arranger Frank Hunter played lead trombone on this last record date.

Elliot still had to contend with the heavy resistance from Columbia records. In the Down Beat interview, Elliot added, “The record companies are neglecting bands, they’re making them cut the same pop ballads that all the big singers are doing. A band vocalist can’t compete with name vocalists with those 40-man backgrounds, so naturally the band records don’t sell as well. Bands should be cutting more originals, things that are strictly instrumental pieces and which don’t have to go out and compete directly with the big vocalists.”

During his time on Columbia Records, he also made record transcriptions. He had done many recordings for Associate Transcriptions in 1946 and 1947. Like all the bands, his studio output ceased during the 10-month AFM recording strike of 1948. He had done many recordings for Columbia while at the Hollywood Palladium immediately before the strike. From October 1949 to mid-1950, he found recording work for such transcription programs as Here’s To Veterans.

On November 17th, the band met in Columbia’s Studio D at 799 Seventh Ave. in New York and made a few cuts for an upcoming 1950 March of Dimes transcription program. Because of Elliot’s childhood struggle with polio, he was named chairman of the “bandleaders’ division” of the March of Dimes for 1950.

By the fall of 1949, the band saw the following changes in personnel over the past two years: Howie Mann (Tittman) of Glendale, Long Island, took over the drums in September 1947. In May 1948, Fred Schmidt, for years first French horn with the Indianapolis Symphony, replaced John Saint-Amour, who joined the Columbus, Ohio Symphony. Johnny Dee briefly left the band to help manage the family hotel in Atlantic City after his father became ill. Stan Kenton found him and berated him for leaving the business. Dee called Elliot, and he got his job back as first trumpet.

In November 1948, the same time as Dee’s return, Joe Techner took over the trumpet jazz chair replacing Walt Stuart. Red Rodney had recommended Joe for the position. During the war, Joe had been with the Bob Sheble band and played in the 106th Army Ground Forces Band at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. Also, in November 1948, Howie talked Elliot into getting Bob Karch as relief piano on the band, thus letting Elliot front the band in his flashy sport coats. Until Karch came, the band only had a rhythm guitar to fill in when Elliot was not at the keyboard. Joe Delaquilla joined as French horn during this time. In June 1949, Bobby Hunter came on board playing trombone, and Frank Hunter officially joined the band as a full-time arranger. This was in addition to Mulligan, of course.

Top (left to right): Gerry LaFurn, Gene Hessler, Ollie Wilson

Bottom (left to right): Sy Berger, Vince Forchetti, Mert Oliver

Elliot set his eyes for Bop City on New York’s Broadway and the Blue Note in Chicago. “If we do play those spots a lot of people will be knocked off their chairs at what they hear,” Elliot promised. As it turned out, as Merle Bredwell later recalled, these were the two most outstanding performances of the road band.

January 5, 1950 New York Daily News

Elliot began 1950 with three weeks at Bop City with Frankie Laine and the Slam Stuart Trio. Michael Levin found the band more mature and gave the band an overall impressing review. The Bop City gig was also reviewed by Variety who found the band performing tricky musical patterns with some unusual sound effects. The arrangements were sometimes too ornate and Mulligan’s “Elegy for a Man” was pretentious. Here is January 12, 1950 recording of Elliot Lawrence at Bop City.

Bop City restaurant menu. Courtesy Howie Mann

After Bop City, some highlights of the band’s tour was visiting Virginia, North Carolina, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Missouri. The Newark Advocate reported, “concentrated through the South, this latest tour proved the most successful the orchestra has had since its organization three years ago. Dixie dancers hailed the band as the most modern and danceable crew to go below the Mason-Dixon line in some years.”

The Newark (Ohio) Advocate March 9, 1950

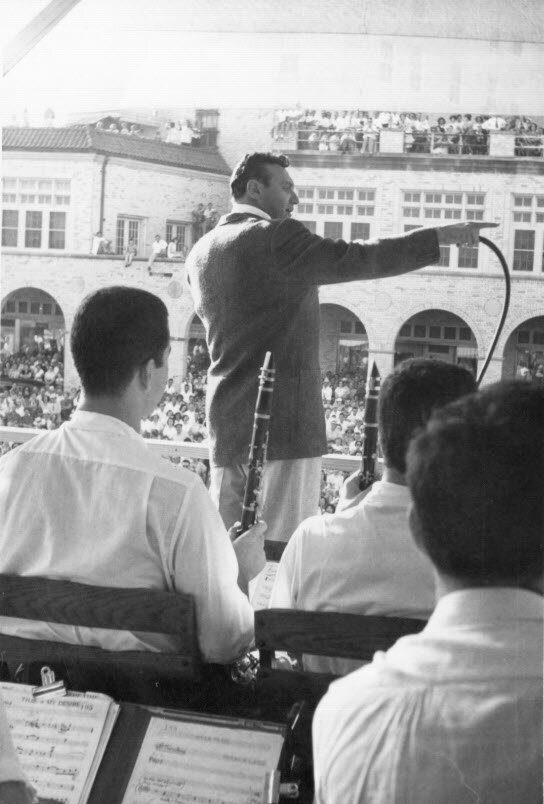

Elliot’s band performed during the opening game of the Phillies at Shibe Park. Elliot and arranger Bix Reichner had joined together to form the Elliot Music Company as an outlet for their compositions and arrangements. For the occasion, Elliot and Bix wrote “The Fightin’ Phils” that sold over 5,000 copies during the 1950 season. The recording was intended to be strictly a “publicity stunt” and the band never actually recorded the record. It was recorded by the Delaware County String Band.

Elliot’s conversion to bop was short-lived. On February 1, 1950, Manie Sachs left Columbia Records and joined RCA and quickly became a vice president. Columbia replaced Sachs with Mitch Miller as their A&R man. Sachs took many artists with him to RCA. By May 1950, Elliot was signed with Decca to churn out college dance ballads. Following the same pattern when he first got a Columbia recording contract, he immediately set out to disassociate himself from bop. In Down Beat he set the record straight, “Ours is not a bop group and we don’t like boplicity to that effect. Primarily, we’re a dance band and we love it. Like every group of musicians, we like to get out some special non-dance arrangements for a concert once in a while, but that’s not our bread and butter… When more musicians concentrate on playing good dance music, I believe the music business will again become one of America's big money makers.” Elliot said the Decca recordings weren’t very good.

Elliot appeared at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan for the three-week stay from May 17th to June 6th with headliners “Mr. Rhythm” Frankie Laine and “The Latest Rage” Pattie Page.

May 26, 1950 New York Daily News

On June 7, 1950, Elliot began recording for Decca with studios at 50 W. 57th St. in New York. At the front of the small studio, watching over the musicians, was a famous picture of an Indian with outstretched arms and a tear coming down his cheek. A sign above him stated, “Where’s the melody?” If they boys in band felt they were strangled at Columbia with sleepy ballads, then Decca was worse. Decca was only interested in building Elliot up as a sweet band. The selections badly plied to the college crowd and would be enough for two 10” LPs and 12” LP reissue entitled College Prom. A Down Beat review noted, “Mostly, this LP is a melange of dull, deadly tempos, male choirs, and Lawrence’s harmless piano playing, though Roz Patton sings well in her solo chores.” Neither Elliot nor his band enjoyed Decca’s muffled and flat ballad recordings.

Stan Weiss recalled the Decca college albums and noted, “Elliot wrote them a la “The Four Brothers” voicing with myself playing lead tenor and Herbie Steward filling in jazz obligatos on the alto.” More about the Four Brothers and Steward later in this article.

If it weren’t for drummer Howie Mann and his friend Rudy Van Gelder, most of the band’s best material would have been lost. In 1950, Howie bought a Pentron open-reel tape recorder. He carried it to one-nighters and sat it next to him during performances. A few of the rare one-nighters survived from these ten-inch reels. Howie also recorded banter and made skits on his portable recorder with band members when they weren’t on the band stand.

Ampex 300 tape recorder. Wikimedia Commons

Howie befriended Rudy, an optometrist living with his parents at his 25 Prospect Ave., Hackensack, NJ. Rudy later abandoned optometry to open a state-of-the-art recording studio in Englewood Cliffs and became one of the most sought out recordists of jazz material, much of it on the Blue Note and Prestige labels. Howie Mann and Phil Urso would often stop by on their own time to jam in Rudy’s make-shift living room studio with other notables, including pianist Bill Triglia and trumpeter Tony Fruscella. Rudy dubbed airchecks, or “airshots,” of remote broadcasts by the band on a cutting-edge Ampex 300 tape recorder.

The band appeared at the Pleasure Pier in Galveston from August 18th to September 4th. Here are recordings of Elliot’s Pleasure Pier appearance. Note the Gerry Mulligan tune “Apple Core,” is called “The Texas Hop.” On August 20th, Elliot skipped a day at the Pleasure Pier to rejoin Frankie Laine for a free concert at the Murdoch Pier in Galveston, Texas.

Above: free concert Elliot Lawrence and Frankie Laine gave at the Murdoch Pier in Galveston, Texas. Sunday, August 20, 1950.

Roz and Elliot at Galveston’s Pleasure Pier, August 1950. Photo by Stan Weiss.

In the fall of 1950, personnel infused the band from Woody Herman’s Second Herd that had recently folded. New additions included Rob Swope, Earl Swope, and Ollie Wilson, all trombonists; Mert (Bass Fiddle) Oliver, Herbie (Alto Sax) Steward, and Buddy (Tenor Sax) Savitt. In September 1950, Danny Riccardo joined the band as male vocalist, replacing Jack Hunter. Riccardo, who was 5‘8” with black hair and brown eyes, couldn’t read music.

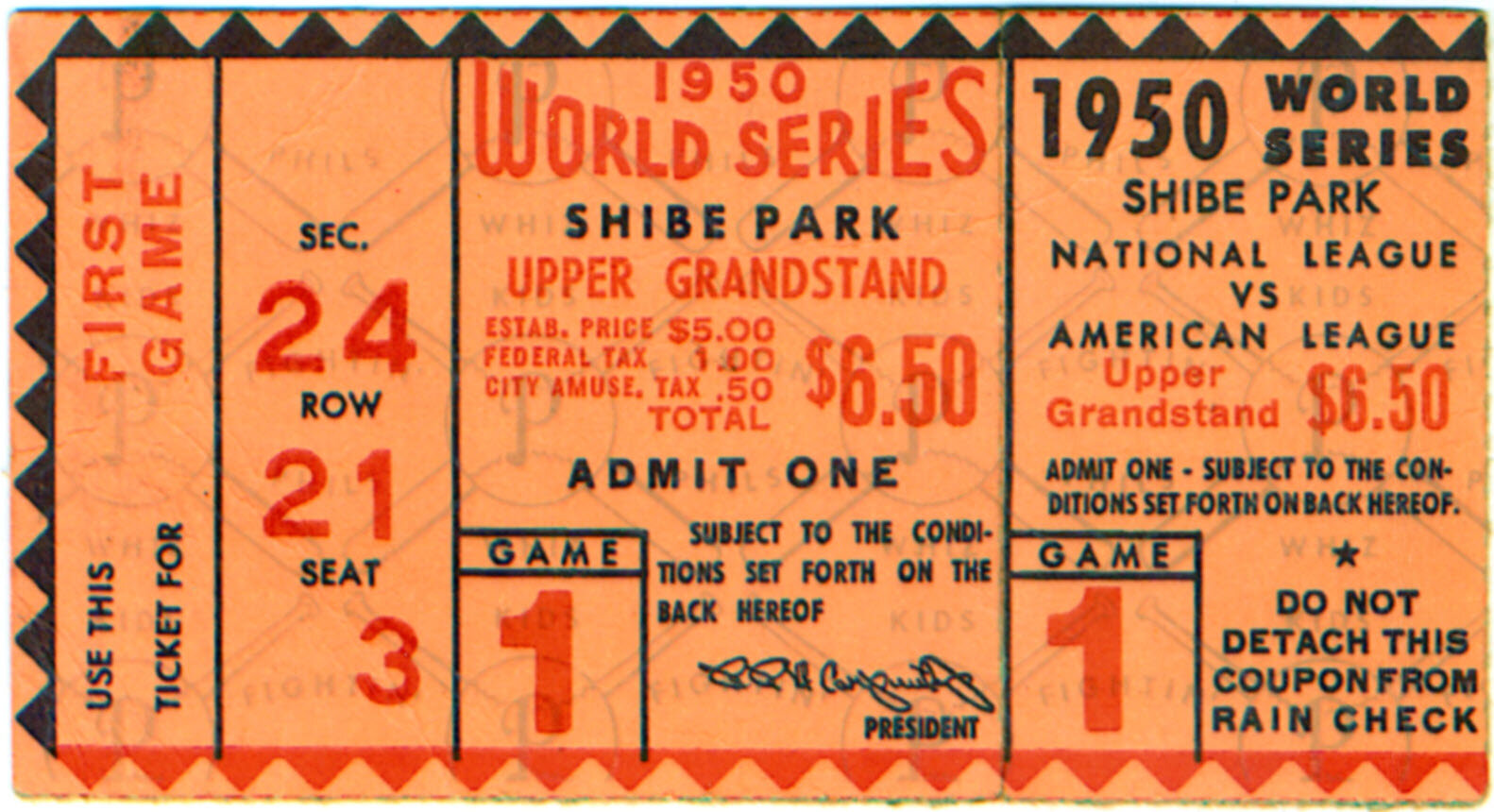

Stan Weiss remembers October 1, 1950 - the date of the last game of the baseball season. On this day, the boys in the band were glued to their radios while driving to a gig. Dick Sisler scored a three-run home run in the top of the 10th inning against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, sending the “Whiz Kids” 1950 Phillies to the National League pennant. Everyone in the cars cheered because of a promise made by Phillies owner Bob Carpenter back in the Spring when the band opened the season. Carpenter promised that if the Phils won the pennant, the band would perform the opening game of the world series. The Phils did open Game 1 of the 1950 World Series at Shibe Park in Philadelphia.

Howie Mann’s ticket for the 1950 World Series

Shibe Park early 1950s

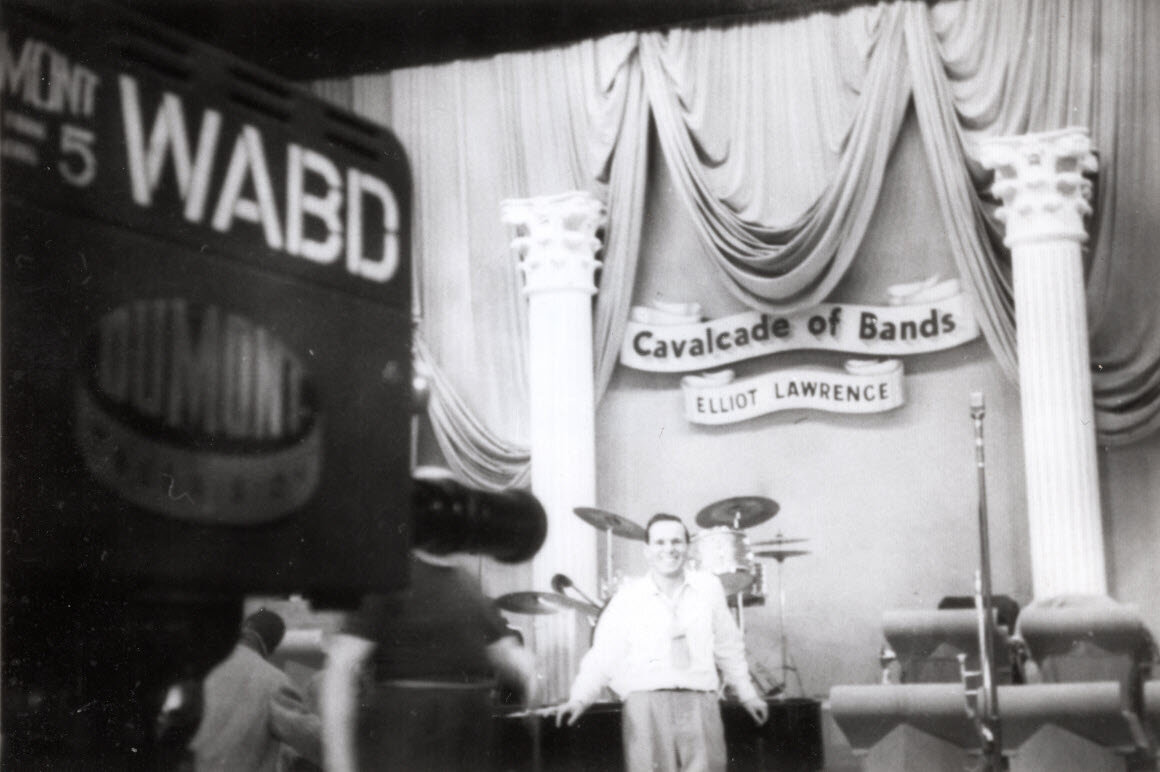

Rudy Van Gelder recorded the band’s December 5, 1950 Cavalcade of Bands broadcast on Dumont television.

Cavalcade of Bands TV broadcast.

The Cavalcade of Bands broadcast was a great accomplishment for Elliot. Although it was short-lived, the show was one of the most sought-after venues for entertainers of its time because it would increase band tour audience attendance from 40 to 60 percent. A Down Beat article detailed the work put into it, “Rehearsals ran on a railroad schedule with the four acts gone over from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. and the band from 1:15 to 3:15 p.m. on Monday. Tuesday the acts are rehearsed with a piano and music director [Sammy] Spears from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., where the band comes from 1 p.m., while the band comes in from 1 to 4 p.m. There’s a “dry” rehearsal for acts and commercials from 4:15 to 5:15 p.m.; dress rehearsals from 6:15 to 7:15 p.m.; by 8 everyone is making up, and by 8:55 the entire cast is assembled on stage. It is generally at this time that producer [Henri] Gine breaks the tension by requesting the whole group to say “cheese” (for a smile) and by making them all chant in unison, ‘How now, brown cow?’ Does this really break the tension? Well, to date, the curtain has always come up on the corps of genuinely relaxed musicians.”

The article added, “The band’s seating is tricky, since the sections have to be slightly separated for easy photography, and yet appear together.” Elliot Lawrence added that “the most important thing about TV for musicians is that it always keeps them on their best behavior. Carelessness and boredom are out, since you never know when that camera is going to dolly in for a closeup.”

Note little dog “Pres” on piano

The TV broadcast featured an additional member of the band, “Pres,” a little dog named after Lester Young that sat atop Lawrence’s piano during performances. The band picked Pres up in Sauk City, Wisconsin on October 26, 1950, while playing at the Riverview Ballroom. Stan Weiss recalled that everyone enjoyed Pres. The band would call him, and he would come running - sliding across dance floors, making everyone laugh hard. Elliot recalls he went with Roz after the band’s break-up.

Elliot Lawrence band at the Blue Note

Elliot spent the last week of 1950 showcasing his ex-Herman personnel at the Blue Note. Elliot’s band was now at its peak of creativity and talent, and the 88-er had everything he wanted: seasoned professional sidemen, Mulligan arrangements, and the Blue Note. Of all the ex-Herman personnel, Elliot spotlighted Herbie Steward. He had been one of the 2nd Herd’s “Four Brothers” - the name of a combo and the most popular tune of Woody’s – after Woodchopper’s Ball. Under Woody, the combo had included Zoot Sims, Herbie Steward, Stan Getz on tenor, and Serge Chaloff on baritone.

Elliot’s often played “Four and One Moore” (sometimes called “Lawrence Leaps”). This Mulligan arrangement was recorded on April 8, 1949, by Stan Getz, joined by four other tenors (Al Cohn, Allen Eager, Zoot Sims, and Brew Moore) and is based on the Four Brothers (Klinkowitz, pg. 39). At one-nighters, Elliot would often jokingly introduce his version as “Three Gents And A Gentile,” performed in Elliot’s band by Herb Steward, Stan Weiss, Buddy Savitt, and Mike Gordon (Goldberg). Herbie Steward joined Elliot in March 1950, playing the alto sax.

Despite these treasures, Howie Mann told me that he wished there were a better representation of the sound of the band. The band sounded much better than the surviving recordings. He lamented that the music was there but the technology wasn’t.

Howie believed the best material surviving of the band is on the numerous reels of Mutual radio broadcasts at Frank Dailey’s Meadowbrook in January and February 1951. Van Gelder recorded the broadcasts over WOR-FM. From these recordings, listeners today can hear the following Mulligan arrangements: “Apple Core,” “Bye Bye Blackbird,” “Red Door” (by 1950 it was renamed “Swinging Door”), “A Happy Hooligan,” Jeru (Miles Davis’ nickname for Mulligan), “Mr. President” (in honor of Lester Young), George Gershwin’s “But Not for Me” and “Strike Up the Band” Also heard are “Out of this World” and “Baia.” Stan Weiss recalled that the broadcasts were done with just one microphone. Each soloist would leave their chair, play to the mike and then return to their seat.

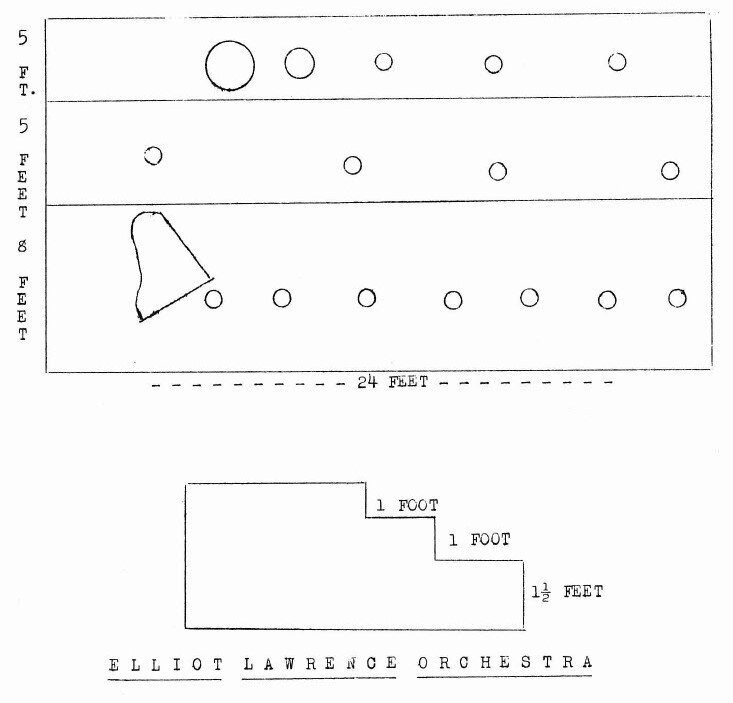

Elliot Lawrence Orchestra seating diagram (Associated Booking Corporation, 1950)

Like so many of the bands, Elliot’s band suffered from drug use. Howie Mann said that he didn’t like what was going on in the band when he left in May 1951, “There were seven members of the band that were addicted to heroin. I’m not going to tell you their names.” Gerry Mulligan’s addiction to heroin is well known. Howie Mann said this problem primarily started with changeovers of band personnel – the influx of the Herdsmen. Howie remembered the band was “one big happy family” and a “clean-cut bunch of guys” until the problems began.

In March 1951, Elliot saw what was happening and tried a media spin, “Because of the bad publicity some bands occasionally get, many parents didn’t like the idea of their sons touring the country with us. Some parents couldn’t believe that it was possible for a band member to live a clean and wholesome life. Sunday morning, if we are on the road and if it at all possible, we stop so that the boys can go to church.”

Nonetheless, all the musicians that I interviewed told me the same stories. Howie remembered a band member falling asleep on Elliot’s shoulder at the Blue Note because of the abuse. Vince Forchetti remembered guys screaming and banging their heads on the walls in their hotel rooms if they couldn’t find heroin or cocaine. They would take up a collection and send someone into another town to bring back dope. Bruno Rondinelli remembered that he and Gerry Mulligan roomed together once in Ohio. Mulligan instantly started walking around the room with a heroin needle stuck in his arm. He told Mulligan it was the last time they roomed together. Mulligan would hunch over in the car after a date waiting for a fix in a hotel room. In later interviews, Elliot readily admitted the drug problem that many in his band had.

In a 1948 article of Metronome, Leonard Feather tried to warn the musicians of the day, “The truth is that today’s marijuana is kid stuff compared with what’s been going on. Marijuana, though illegal, is not a habit-forming or dangerous drug, in the opinion of most doctors. But heroin, morphine and cocaine are other and far graver matters. Their use has spread like a vile disease among an increasing clique of musicians. It only takes a few uses of these drugs to make a helpless addict. You hear that such-and-such a musician has been “busted” (arrested), or that he is trying to “kick” (break the habit), or that he is down to “five caps” (five capsules of heroin per day). It’s not a pretty sight when your favorite horn man, after taking a terrific chorus, sneaks off to a secluded spot, hypodermic needle in pocket, and returns twenty minutes later glassy-eyed, completely out of this world. Fortunately, there are still large numbers of clean-living musicians who haven’t been contaminated, but there’s nothing a junky likes more than to create another junky, who may thus be a source of drugs to him someday when he runs short. Moreover, the depressing professional conditions in which many musicians are forced to live nowadays, and the failure of the public to accept the kind of music they believe in, drives them more and more often to artificial escapes from their neuroses.”

Another cause of the drug use was a false belief that the drugs made a better jazzman. Elliot said that many young musicians thought it was the drugs that made Charlie Parker play so great, and they emulated him (Charlie Parker died in 1955 at the age of 34). Drugs and alcohol also gave some players the ability to be on the bandstand. Elliot told me that Gerry Mulligan once remarked, “I don’t know how Elliot ever did it. How he faced the band without drugs or alcohol.”

Merle Bredwell recalled the effect of the drugs, “For a lot of years there were no heavy drugs, and I would say probably only about the last couple years I knew that some of the heavy drugs had come into life. And it was too bad because some of the individuals were very talented, and I don’t know why they wanted to take the drugs because I don’t think it augmented their talent at all. And unfortunately, a lot of them lost their lives because of it. And I think the closer it came to the time when I did leave, more and more was in use.”